Saturday, April the 14th, 2012

back to: title, date or indexes

Two things serve to persuade me that the Ancient Egyptians were a peculiarly dim-witted rabble.

There is a tendency to regard the great civilisations of the past through rose-tinted spectacles. One thinks of Edgar Allan Poe, writing of “the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome” in To Helen (revised 1836) or Neil Young babbling, of the Aztecs, that “the women all were beautiful and the men stood straight and strong… Hate was just a legend and war was never known” in Cortez The Killer (1975). I think we may safely say that these aperçus are what Ambrose Bierce, using a favourite term, would call “bosh”. What we overlook, with our romanticising blinkers, is the stark fact that much of human history was attended by filth and squalor and hunger and disease and slavery and violence and stink and flies and rats and brutality and terror and mud and ignorance. All that, of course, being your daily lot if you managed to live long enough to experience it, which untold millions, given infant mortality rates, did not.

In view of this bloody awful state of affairs, let us imagine some Ancient Egyptians, broiling one afternoon under a battering sun.

“I have an idea,” says one, “Let's tramp into the desert and build an enormous, windowless, pointy-topped edifice of no practical use whatsoever.”

“I have a better idea,” says the other, “Let's build two!”

Now you or I might have thought of more constructive ways to spend our time. But not the Ancient Egyptians, who went on to build over a hundred of these pointless pointy-topped buildings all over the arid hellhole where they lived. It is all very well to say that they were in thrall to a particularly vicious and mercurial pantheon of gods, but it seems to me that only supports my theory of their fundamental stupidity. Other civilisations, at other times, have also laboured under the delusion that they were ruled by deities we might sensibly consider as nutters, and dangerous nutters at that, but few have built such pointless yet enormous and pointy-topped structures. Others do exist, but not in such profusion as in Ancient Egypt.

Their enthusiasm for wasting their lives in the tremendous effort of building these idiocies is the first thing that persuaded me of their dim-wittedness. I asked myself what could have prompted such tomfoolery, and that led me to the second point. What possible hope could there be, I concluded, for a civilisation that worshipped cats?

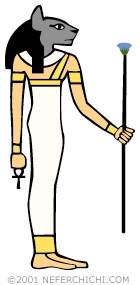

Don't get me wrong, I adore cats. I am definitely a cat person rather than a dog person, and have in the past had several pet cats, and never a pet dog. There are few experiences as conducive to relaxation as being slumped in an armchair with a purring cat dozing on one's chest. But there is a deal of difference between a feeling of affection towards, say, a tabby called Tiddles for whom one is happy to provide bowls of food, and a sense of abject awe and subjection towards Bastet, or Bast, or Baast, or Ubasti, or Baset, the cat goddess of the Ancient Egyptians.

The thing we must always remember about cats is that, for all their grace and elegance and litheness and poise, they are unfathomably stupid creatures. Some will protest that an animal that has so arranged things that it can spend its life eating food from a bowl, sleeping, playing with wool or shoelaces, and chasing small mammals and birds has clearly worked something out. Perhaps so. The average domestic cat lives the life of Riley, and one I find mightily enviable. Given half the chance I would arrange my affairs likewise. But let us keep things in perspective. Far from being a divine being possessed of great power and wisdom, the cat is a halfwit. You only have to observe them, hopelessly chasing birds which—surprise, surprise!—fly away as soon as they come close, or gazing intently at nothing on the wall of a room, or toppling off a windowsill when half asleep, to recognise that, whatever is going on in the cat's brain, it is neither complicated nor astute.

What, then, does it tell us of a civilisation that it elevates the cat to a godhead, and duly worships it? It tells us, I think, that the Ancient Egyptians must have been ineradicably thick. And the evidence is all those pointless pointy-topped buildings, constructed with unimaginable toil in the middle of nowhere, for no pressing reason.

I rest my case.

ADDENDUM : In pondering the sheer ridiculousness of the brain of the cat, I am reminded of a little geographical mystery. In the last decade of the previous century, I often had reason to visit the city of Bristol, the northern part bordering South Gloucestershire to be more precise. Looking at maps, I noticed that on many of them the area had the name “Catbrain” emblazoned across it. Yet whenever I asked a local person about this nomenclature, I was met with blank looks. Nobody I questioned had ever heard of Catbrain, and I concluded that it must have been one of those mapping mistakes which, committed once by a slapdash cartographer, was then repeated by others. I now learn, from the Wikipedia, that Catbrain—or, properly, Catbrain Hill—does actually exist, though I am rather disappointed to discover that the name has nothing to do with the brains of cats and is derived from the Middle English “cattes brazen”, which is a reference to the rough clay mixed with stones that is the characteristic soil type thereabouts. None of which explains why the locals had never heard of it. Unless, of course, it is one of those eerie English countryside locations that are kept secret from interlopers.