Monday, May the 21st, 2012

back to: title, date or indexes

A few days ago, reading A Land by Jacquetta Hawkes, I came upon this;

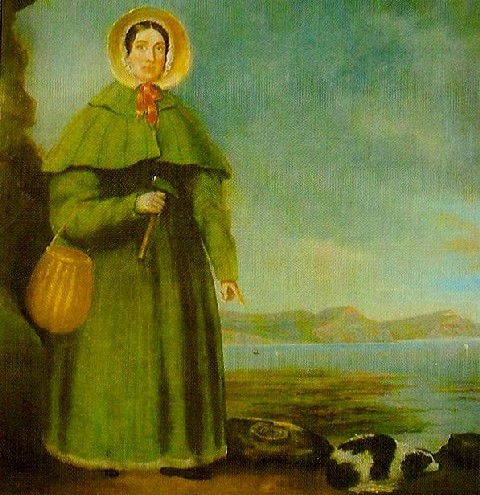

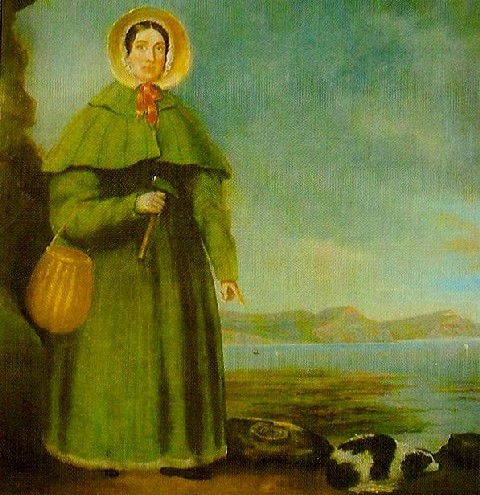

During a Lyme horse-show a storm developed, and after a terrific flash of lightning three people and a baby were seen lying on the ground under an elm tree. The three adults were dead, but the baby, Mary Anning, ‘upon being put into warm water, revived. She had been a dull child before, but after this accident became lively and intelligent and grew up so’. Lyme was already conscious of its proximity to the past; a local fishmonger displayed million-year-old fishes on the slab among the day's catch, while Mr Anning himself was an established fossil hunter, often no doubt bringing back to his shop the fragments of reptilian spines which were familiar enough to have acquired the local name of ‘Verterberries'. From very early years Mary went with him to the cliffs, and when he died, she carried on the trade because she and her family needed the money. In 1811… this twelve-year-old girl found the first complete ichthyosaur… in another two years she had uncovered the first flying reptile or pterodactyl. Perhaps her own favourite was a baby plesiosaur.

This struck me as a fascinating tale—the baby struck by lightning who thereafter transcends her humble background (though she remained poor) by making discoveries that fundamentally altered our understanding of prehistory. The first person to exhume a pterodactyl! I decided then and there to make Mary Anning—of whom I had never heard before—the subject of one of my daily essays. And so, today being the day allotted to her, I was somewhat astonished to note that she was also the subject of today's random article on the front page of the Wikipedia.

“My oh my, what a coincidence!”, I said to myself. Actually, I said it aloud, to Pansy Cradledew, who agreed that it was a startling example of synchronicity. Unfortunately, her use of this term led us to a brief discussion of the works of Gordon Sumner, who had something to say about synchronicity in the years before he turned his attention to playing the lute and having Tantric sex with Trudie Styler. To paraphrase H P Lovecraft, the most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to contemplate the doings of Gordon Sumner for more than twenty seconds. After that, at least within my cranium, there is a sort of automatic shutdown.

When I came to, I pondered whether to calculate the probability of the Mary Anning hoo-hah. There must be millions of articles on the Wikipedia, and I assume the daily random one is selected by some sort of robotic algorithm. My reading of A Land was occasioned by a recent article about it in the Grauniad, allied with the fact that I had a copy of it, a 1959 Pelican edition, inherited from my father. It is a book I have been familiar with all my life, or rather, I have always been familiar with its spine—just as Mary Anning was familiar with her father's collection of reptilian spines—on my father's bookshelves and then on my own. Until I read the Grauniad piece, though, I do not think I had ever opened it. There does appear to be something inexplicably woohoohoodiwoo about the coincidence.

If I had the cast of mind of a primitive savage, or a New Age airhead, I might be tempted to delve into the possible significance of l'affaire Mary Anning, as I am beginning to think of it. Is her shade attempting to contact me from beyond the grave? Am I being coaxed into a study of pterodactyls? Which other neglected books from my father's collection should I at long last take down from the bookshelf and actually read? Such questions could keep a fool's brain occupied for aeons, or at least until bedtime.

Instead, I found myself thinking about the millions of articles on the Wikipedia, and how, today at least, Hooting Yard and the Wikipedia are as one. We both train our beady eyes on Mary Anning. It is true that the Wikipedia has rather more to say about her, and might be the preferred website for spotty urchins who, charged with writing a school self-esteem ‘n’ diversity hub essay entitled What It Feels Like To Be Struck By Lightning And Discover A Fossilised Pterodactyl, hasten to copy and paste swathes of text so they need neither think nor work. (That all too typical essay title, incidentally, would only encourage them to “feel”, rather than to think. History teaching nowadays appears to be a branch of the “journey” undergone by weeping contestants on lack-of-talent shows. Imagine you are a victim of oppression by cold heartless empire-builders wearing pith helmets. How do you feel? OMG it's been an incredible journey, innit.) But while the Wikipedia may be more informative than Hooting Yard, strictly speaking, here the reader will find a slightly different angle of approach, no less valuable in its way.

And then the further thought occurs that perhaps I ought to strive to replace, or at least complement, the Wikipedia, by writing a matching piece for all its millions of articles. Of course I would by no means allow other “users” to edit my work. We don't want the hoi polloi and the ignoramuses to come paddling in our pond, do we? But slowly, gradually, Hooting Yard could become the default reference source on the interweb. I must draw up a schedule, a plan of campaign. I could simply write about whatever subject is the Wikipedia's random article of the day, but it might be better to tackle topics in some order of priority. That way, I can safely place until the very last, after I have addressed millions of other subjects, “Sumner, Gordon : this page is intentionally blank”.