Thursday, June the 21st, 2012

back to: title, date or indexes

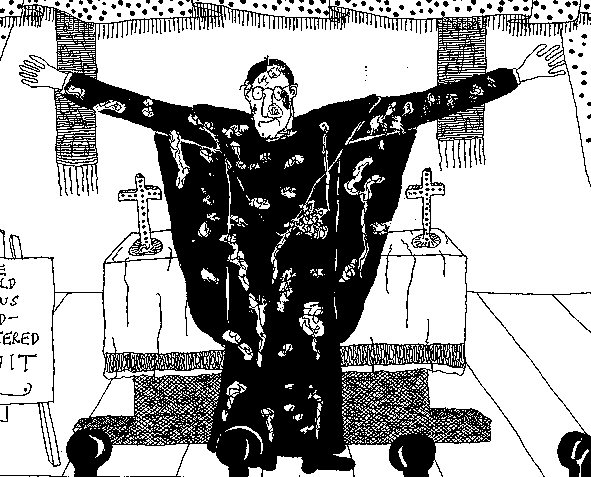

The world-famous food-splattered Jesuit was one of the best loved and most successful variety acts of the interwar years. It is believed that he appeared at every single seaside resort in the land, the grandiose and the dilapidated, in and out of season, and always to rapturous applause. Key to his appeal was sheer simplicity. The curtains would open and there, on stage, world-famous and splattered with food, stood a Jesuit. He would extend his arms, almost in crucifixion pose, and gaze at a point slightly above the heads of the audience. There were no frills, no “business” with props. After a few minutes, the curtains would close, and—barring the inevitable encore—that was that. It was a winning formula, but one which, alas, could not transfer to radio, where so many of the stars of variety theatre went on to find fame and fortune.

Throughout the years of his greatest popularity, roughly the decade from 1925 to 1935, the world-famous food-splattered Jesuit managed, miraculously, to preserve his anonymity. We still do not know for certain who he was. We do know, in spite of rumours put about to the contrary, that he was a single, particular individual, and not a series of different Jesuits. This charge was first levelled in a scurrilous newspaper story. In the Daily Voodoo Dolly for the sixth of September 1929, a hack named only as “Our Seaside Resort Reporter” claimed that the original world-famous food-splattered Jesuit had been killed in an accident (picnic, lightning) and replaced by at least seven other Jesuits, who took it in turns to appear at the end of piers, splattered with food. This farrago of nonsense was comprehensively demolished by investigative variety theatre reporter John Pilge, a man who knew his onions.

But even Pilge was not perfect, and it seems he was the source of a common misapprehension of the nature of the Jesuit's performances. Oft repeated by nincompoop wannabe historians of the seaside variety theatre, this is the idea that the Jesuit stood on stage, initially pristine in his soutane, and that he was splattered with food by members of the audience pelting him with eggs, fruit, cuts of meat, soup, ketchup, ad nauseam. So let me be crystal clear—there is not a shred of evidence that this was ever so. More than that, it belies a fundamental misunderstanding of the entire point of the act, and the reason it was so wildly popular, to wit, that the Jesuit simply stood there, stock still, arms outstretched, faintly holy, world-famous, and food-splattered.

There was an art to these performances which we lose sight of in our modern fast-moving age of pap ‘n’ twaddle. It would be a mistake to think that the Jesuit was nothing more than a messy eater with the table manners of Kafka, who simply allowed various stains and spillages to accumulate upon his soutane. Anybody could achieve that, with persistence, determination, slapdash eating habits, and the shunning of laundry. In fact, there was for a time a rival act known as the world-famous bacon-and-egg-besmirched nun. Though a woman of fine manners and terrific personal hygiene, she was bedizened by the lure of the end of the pier limelight, and dedicated herself to allowing much of her fried breakfast to fall upon her habit. It was an effort of will not to send it straight to the laundry, but she gritted her teeth and prayed, and took to the stage. In itself hers was a fairly enchanting act, as she knelt in an attitude of devotion, clutching her rosary beads, displaying her stains of egg yolk and bacon grease. But she was viewed, with justification, as a copycat, and audiences failed to warm to her. She later achieved a measure of success with a completely different act, involving tea-strainers, coat-hangers, and performing monkeys.

The genius of the world-famous food-splattered Jesuit, on the other hand, was that the splattering was carried out, backstage, immediately before each performance. He would remove his soutane, lay it out flat on the floor, and proceed to splatter it with whatever foodstuffs came to hand. He would chuck eggs or fruit at it from across the room, drizzle it with soup and broth and slops and sauces, and shower it with bread- and biscuit-crumbs. Although there is no evidence that Jackson Pollock ever witnessed these preparations, it seems inconceivable to me that he could ever have arrived at his action painting technique without first having watched the world-famous food-splattered Jesuit.

Though there is common agreement that he was, beyond all reasonable doubt, a Jesuit, and food-splattered, several latterday commentators have wondered about that “world-famous” bit. Given that he is not known ever to have performed outside the seaside resorts of his own country, they ask, is there any truth in the claim that he was famed around the world? This was the interwar years, remember, when communications were technologically primitive compared to our own era. How would a variety theatre aficionado in far flung foreign parts ever hear tell of the goings on at the end of a rickety pier in an out of season seaside resort in our blessed land? It is a pertinent question. But it ignores the decisive role played in the world-famous food-splattered Jesuit's career by his manager.

“Colonel” Tom Emersonlakeandparker was a rogue and a rascal, and an impresario of genius. It was he who first saw the potential of that pristine black soutane, saw it as a blank slate upon which food could be splattered, and then displayed, as in a tableau vivant, to an adoring public. All he had to do, he realised, was to find the perfect Jesuit, first to do the food-splattering, then to stand still with outstretched arms for ten minutes or so upon a seaside stage. By all accounts, he searched for over six years before finding his man—a man whose name still remains a secret. At the first few appearances, billed as the Food-Splattered Jesuit, the act was a flop. But rather than ditch his choice of Jesuit, which he might easily have done, the “Colonel” instead appended “World-Famous” to his stage name. It was a stroke of genius. Crowds thronged to see a figure who was already—they thought—a legend. They were not disappointed, as who could be? Certainly, in today's entertainment-saturated world, we fail to register just how impoverished we are. In the era of multi-channel television and YouTube and a populace with the attention span of a gnat, we ought to be crying out, in our millions, for a variety act as spiritually enriching as the world-famous food-splattered Jesuit. Perhaps a young tyro Jesuit with a burning desire to entertain the masses is reading this. He will know what to do.