Wednesday, June the 29th, 2005

back to: title, date or indexes

Those two great modernists, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, were exact contemporaries, both born in 1882 and dying in 1941. Their reputations have survived, indeed prospered, in the twenty-first century. The same cannot be said of a third writer who shares those dates of birth and death, the now forgotten Minnie Crunlop. But was Minnie more modern than Jim and Ginny? Some critics think so. Here is Tadeusz Glob: “Crunlop was a monomaniac who stuck to a preposterously limited subject matter, but I am convinced that her name will ring down the ages, outlasting Homer, Beowulf and the Bible.” Praise indeed, from the man who dismissed as “clots and nincompoops” nearly every writer of note from the seventeenth century onwards.

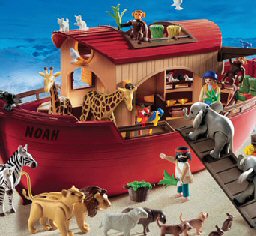

Glob is certainly correct to refer to Crunlop's “preposterously limited” range. In fact, all she ever wrote were stories featuring the sons of Noah. It is true that she placed Shem, Ham and Japheth in an astonishing variety of settings, but no other characters feature in her work, except for occasional appearances by a fictionalised version of Suez Canal visionary Ferdinand De Lesseps (1805-1894).

If her work is unconventional, so too her career. Minnie Crunlop only began to write in the last decade of her life, on the fourteenth of January 1931, to be precise. It was on the cold morning of this day that she wrote, from beginning to end, the famous story “Shem, Ham And Japheth Join A Knitting Circle” which appeared in the inaugural issue of Messbang's Popular Magazine Of Catastrophic Flood Fiction.

Crunlop had met the self-styled delugeist Orthek Messbang a few months previously. They had a passionate yet enigmatically unconsummated affair. Among the sweet nothings he whispered into her ear was his plan to publish two periodicals devoted to his pet topic, one containing fiction and the other fact. After a stroll among the bougainvilleas and fountains, Crunlop promised to pen a story based vaguely on Noah's Ark. On her way home, she bought a Bible. She had never read it before. Locating the text she needed in Genesis, she tore it out and threw the handsome volume into a waste chute. Over the next week, she memorised the story of the Flood, and thus began her singular literary career.

Messbang's magazines folded after just one issue each. He swept into Minnie Crunlop's parlour to announce their failure, only to find her scribbling away at her second tale, “Shem And De Lesseps Go Pig Hunting”.

Messbang : Darling! I am ruined! My periodicals are no more! Cease writing!

Crunlop : O dearest one! I could not stop even if I wanted to, for I feel the Muse inspiring me! I am going to spend the rest of my life writing strange little stories about Noah's three sons! It is my destiny!

Messbang : Love of my life, have you taken leave of your senses? Only I would publish your deranged jottings, and now I am undone!

These were Orthek Messbang's last words. He flung himself from Minnie Crunlop's window on the fifth floor of her shabby apartment building and was impaled on an iron spike in the street below. So consumed was Crunlop with the vivacity of her tale-telling that she did not hear the ungodly siren of the ambulance which carted her lover to the morgue. She remained at her escritoire, pencilling in a frenzy, until her second story was finished, when night was drawing in.

Messbang had abandoned a wife, now his widow, in Dusseldorf or a similar city, who took some solace in the fact that his final words were prophetic, for it seemed that no one was interested in publishing Minnie Crunlop's second story. Nor the third, nor the fourth. She had hit her stride now, and spent every Thursday writing, from dawn till dusk, conjuring new adventures for her heroes. She had plucked the three sons of Noah from that overcrowded ark, and was pitching them into new and dazzling adventures. “Shem And Ham Visit The Glue Factory”, “Japheth Is Buried Alive” and “De Lesseps And Ham And The Mysterious Bag Of Soil” were all written before the end of the year. Crunlop occasionally tried hawking them to publishers, without success, but every door slammed in her face seemed to inspire her to new heights of invention. She continued to eke a living by boiling and darning flags, as she had done since her release from prison just before the Great War.

Critics today are understandably coy about Minnie Crunlop's life before she became a writer. The received wisdom is that her criminal past has nothing to tell us about her work, that we can separate the murderous psychopath from the story-teller, as if they were two distinct Crunlops. Indeed, it is difficult to square the gore-drenched cut-throat skulking in the alleyways of Dubrovnik, or somewhere like Dubrovnik, with the pencil-wielding genius of the shabby apartment building. We must, I think, be grateful that King Vincenzo announced an amnesty just before the war. Cynics say the King expected all those he released to perish on the battlefields, and most of them did, but Minnie Crunlop survived, for she spent the war years hiding in a hayloft near an orchard, creeping out at night to eat her fill of pears and gooseberries and drinking from a spigot by the side of a barn.

Was this hayloft Crunlop's ark? She shared it with a pair of geese and a pair of stoats, or at least that is what she said later. But then she claimed to have named the geese Shem and Japheth and the stoats De Lesseps and Ham, and this is unlikely, given that she was, as we have seen, Bible-ignorant at this point. In her last illness, when her brain was a fuming hallucinatory miasma, she told all sorts of stories about her time in the hayloft, indeed she spoke of little else. Incoherent babble it may have been, but clearly this period—after the killings and before the stories—was of great significance for her. Over the years there have been attempts to convert the wartime sanctuary into a Minnie Crunlop Museum or Memorial Library, but no one has ever been able to identify the actual site, given that there are literally dozens of haylofts in barns near orchards in the country.

Curiously, her writings give no clues. Throughout the canon, there is no mention of any kind of agricultural building. The reader will find plenty of gaudy palaces, space stations, skyscrapers, futuristic pods, Transylvanian castles, urban dystopias and Victorian drawing-rooms in Crunlop's fiction, but no barns in farmyards. Nor will one find an ark, of course. The only story that nods in a seafaring direction is the elegiac “A Rowing Boat And Its Oars” (1936), the first of Crunlop's works to win a prize. She had, at long last, found a publisher, in the form of Doctor Gillespie's Pedantic Register & Gazette.

“Doctor Gillespie” was a fictional character who purported to edit—and write most of—this weekly periodical, which was heavily illustrated with mezzotints by the mezzotintist Rex Tint. It was Tint who recommended Crunlop to the genuine, non-fictional editor, a secretive plutocrat with a piratical eye-patch who was to become her sole publisher.

In the remaining four years of her active career, the tales poured out, some of them only fifty words long, some close to novellas. It was an age of anxiety, as Europe edged once again towards war. Minnie Crunlop took to sporting an eye-patch in homage to her mentor. She went to visit De Lesseps' Suez Canal, where she wrote the ground-breaking “Ham's Rakish Sneer”. She penned anonymous fan letters to Hollywood actor Claude Rains. Her shabby apartment building was given a new lick of paint, or paints, all mauve and yellow and a startling cerulean blue. She pondered writing a new type of story, one that would feature Neville Chamberlain, but abandoned it after a long and earnest discussion with Rex Tint in the dining room of a majestic hotel, where the pair of them ate soup, crackers and potted paste, before running away without paying the bill. She exchanged her collection of pencils for a pen with an unbreakable nib, and promptly broke the nib. She was praised in an essay by Kapisko, and Larch painted her portrait, and King Vincenzo's son, the new King, also called Vincenzo, presented her with a medal. She wrote a marvellous, tragic, tear-stained tale called “Japheth Is Buried Alive, Again”. Her hair turned white.

And then, on the fourteenth of January 1941, ten years to the day since her writing career began, she was engulfed by a daze, a daze that could have been mistaken for a coma were it not that within her daze she babbled incessantly, about the hayloft and her geese and her stoats, and little else, and she never again picked up her broken pen, nor any of the pencils she had retrieved from a rubbish tip, and she babbled away in her daze for forty days and forty nights, ark time, and then she passed away, and now she is all but forgotten, so you must mark her name, and mark it well. Minnie Crunlop!

Hooting Yard on the Air, June the 29th, 2005 : “Shem, Ham, Japheth and Minnie Crunlop” (starts around 00:14)

Hooting Yard on the Air, July the 26th, 2006 : “The Weird Spinney” (starts around 16:57)