Bucephalus

Sunday, February the 26th, 2006

back to: title, date or indexes

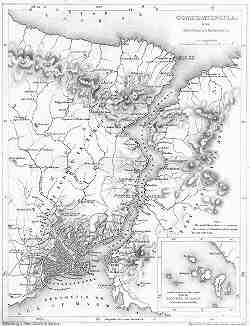

The weather was foul on that day in the Ancient World, that Thursday when an unaccompanied horse cantered to a halt at the bank of a mighty waterway. The horse was Alexander the Great's steed Bucephalus, sent by the Macedonian hero for a recuperative holiday. The river was the Bosphorus, the strait between the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara.

Alexander was a firm believer in horse holidays. When young, Bucephalus had been skittish and temperamental, frightened of his own shadow, and Alexander's ministrations had becalmed him, but even as the mature horse he was now, there were times when he needed a break from campaigning and battle. Thus it was that Alexander had waved him off to—as he put it—“enjoy the mysteriously sultry atmosphere of a few nights by the Bosphorus”*.

Bucephalus

But it was not night-time, sultry or otherwise, when Bucephalus arrived at his destination. It was day, bleak, grey, and wretched, and the majestic horse stood still at the river's edge, snorting. Alexander the Great did not expect him back in Macedonia for a week. Remember this is the Ancient World, so such landmarks as line the Bosphorus as the Galata tower, the palaces of Dolmabahce, Ciragan, Yildiz, and Beylerbeyi, the Rumeli and Anatolian Fortresses, and the Kuleli Military High School had not yet been built. Bucephalus began to trot, following the river's course, hoping to find a field where he could have a restful time munching nutritious foliage.

It was late afternoon on that Thursday when the horse decided to rest, and planted his hooves in the mud at the edge of the Bosphorus where today one finds the Bogazici suspension toll bridge. He noticed a churning in the waters of the mighty river, and turned his horse-head to look more intently. He was astonished to see a tangle of cephalopods thrashing around in the river, cephalopods large and small, octopuses, squids, cuttlefish and chambered nautiluses, emitting clouds of ink, tentacles flailing. What were they doing upriver, rather than in the dark, cold abysses of the sea? Were they lost, and did this explain their frantic activity? Cephalopods are probably the most intelligent of invertebrates, with huge pulsating brains, and it is easy to imagine that the realisation of being lost in the Bosphorus could induce panic among them.

Bosphorus

Bucephalus had devoted his life to the service of Alexander the Great, but now he wondered how he might help these strange sea-creatures, so much more ancient than he, or Alexander, or even the Ancient World in which he lived. Could he somehow take them all back to the sea, and release them into the vast pitiless oceans that were their natural home, from the warm waters of the tropics to the icy chill of the poles? Being a horse, Bucephalus could not think how he might lay a trail of plankton and krill for the cephalopods to pursue. He could not think of any way at all to lead them to the sea. So on the spur of the moment, he decided to gallop back to Macedonia, to fetch Alexander the Great, confident that his master would know exactly what to do.

Alas! When he got to Macedonia, Bucephalus was told that Alexander was in the ancient Phrygian capital of Gordium, puzzling out how to undo the Gordian knot so he could become the future King of Asia. So the brave horse charged tirelessly onward, collected Alexander—who had either worked out how to undo the knot or just hacked it apart with his sword, depending on whose story you believe—and sped with him all the way back to the Bosphorus.

When they got there, they found no sign of the cephalopods. If a horse can feel sheepish, Bucephalus certainly did. He watched as Alexander dismounted and strode off, his armour clanking, into the field where the horse had munched his lunch. The Macedonian warlord plucked a plant from the earth and brought it to over to the horse.

Cephalopods

“This, Bucephalus, is henbane. It is not only the bane of hens, but of horses too. One day, when the Ancient World has passed away and the new times are known as mediaeval, it will be used in the brews concocted by witches to cause visual hallucinations and the sensation of flight. This I know.” Alexander smiled and patted Bucephalus affectionately on the mane. “Poor deluded horse,” he continued, “You saw no cephalopods. You were seeing visions of things that cannot be. Come, let us return to Macedonia at a canter, and I will give you healthy hay to eat.”

And as night fell on the sultry, mysterious Bosphorus, Alexander and Bucephalus began their long journey home. And in the depths of the river, the waters stirred, and a squid slithered through a tiny crack in a riverbed rock, its black, fathomless, malevolent eyes piercing the underwater world, long long ago, and far into the future, for eternity.

*NOTE : Alexander the Great is here paraphrasing a line from Anthea Bell's translation of Twilight by Stefan Zweig, published by the Pushkin Press, and highly recommended. There is a photograph of Herr Zweig and his wife tucked away in the Hooting Yard archive for August 2004.

FURTHER NOTE: If you want to keep up with the very latest in the world of squids, nautiluses, octopuses and cuttlefish, I recommend Cephalopod News.

An audio version of this story, declaimed by the author, will shortly be available as a cephalopodcast.

Hooting Yard on the Air, March the 1st, 2006 : “Bucephalus and the Cephalopods in the Bosphorus” (starts around 00:27)

Hooting Yard on the Air, June the 2nd, 2016 : “"Experiment : Procure a wide-mouthed bottle, an..."” (starts around 10:54)