Sunday, April the 2nd, 2006

back to: title, date or indexes

Q—Did Dobson ever receive death threats from a vengeful maniac?

A—Yes, he did. When he was living in the village of Mustard Parva he turned his attention to rural matters and wrote a pamphlet—now out of print—entitled My Revolutionary New Method Of Moving Sludge Around The Countryside. A copy fell into the hands of the village sludge person, a peasant whose job it was to push his barrow of sludge along country lanes, from a field to a barn, or from a ditch to a coppice, or from a farmyard to a pond*.

The village sludge person was unable to read, but was so entranced by the picture on the cover that he took the pamphlet to Mistress Spinoza, who taught the village urchins.

“Hail, oh sludge person!” she cried, as he crashed into her schoolroom, holding the pamphlet as if it were a hot pie, “I shall lock the urchins in a dark cupboard so they do not get up to any mischief while I read Dobson's latest pamphlet to you!”

As soon as her forty-seven snivelling, whimpering charges had been safely confined, and heavy iron bolts drawn across the cupboard door, she rattled through the pamphlet as the sludge person listened, at first with curiosity, then with growing rage.

Too many of today's peasants simply do not know how to move sludge, or indeed any other kind of rustic matter, along the lanes of our bosky and idyllic countryside, wrote Dobson, so I have invented a fantastic new technique, wholesome yet valiant, impeccable yet louche, which, if put into effect, will utterly transform the movement of sludge from, say, a barnyard to a trench, or vice versa. Mark my words, he continued, as a red mist descended over the listening sludge person, unless the peasantry follows this incredibly exciting new scheme, our land will fall into desuetude and ruin. Do not say you have not been warned!

Mistress Spinoza handed the pamphlet back to the sludge person and steered him into the kitchenette attached to the schoolroom. She made him drink a draught of Doctor Gillespie's Brain Calming Syrup, and as he tottered away on his spindly legs, she hoped that his anger would subside.

Q—Did his anger so subside under the influence of Doctor Gillespie's excellent syrup?

A—No, it did not, for unbeknown to her, Mistress Spinoza had bought a rogue bottle of the syrup, laced with ingredients which served only to inflame the sludge person's temper. He went directly from the schoolroom to Dobson's cabin, and hammered on the door like a crazed thing.

Dobson was not amenable to unexpected visitors. Like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, he had had his Person from Porlock moments, and he had taken to stuffing his ears with rags while at work. Imagine then, how a hot-tempered peasant bashing on Dobson's door would become increasingly splenetic as the hours passed. He was nothing if not persistent, this sludge person, for he continued to beat his hairy fists on the door for three hours, until exhaustion, agony, bruising, blood, and broken bones made him stop. All the while, a deliberately deafened Dobson was writing another pamphlet, this one on the subject of X-ray vision, dust, and fruit pastilles. The sludge person lay slumped in the doorway for a further hour before crawling back to his shabby hovel, where he sprawled on a mattress riddled with weevils and other tiny scurrying beasts, plotting Dobson's downfall.

Q—May I ask what angered him so?

A—You may. The pamphleteer's revolutionary new method of moving sludge around the countryside threatened him. It threatened his livelihood, but more importantly it threatened his pride. The sludge person had inherited his job from his father, who had inherited it from his father, who had taken the job over from his father, and so on, yea unto generations past. So long as sludge had been moved around the lanes of Mustard Parva and thereabouts, this peasant's family had been in the thick of it. Now along came this pamphleteer with his peanut-shaped hat and his Paraguayan Detective Inspector's jacket, and not only did he have the temerity to live in the cabin where once Old Mother Weltschmerz had read the runes and done weird things with hamsters, but he was putting it about that there were other, better ways to move sludge.

And so, as I said, he plotted Dobson's doom. He began, next morning, by going back to the schoolhouse, just as Mistress Spinoza was letting the urchins out of the grim dark cupboard.

“Top of the morning to you, oh sludge person!” she yelled, “Would you like me to read Dobson's pamphlet to you once again?”

The sludge person explained that, on the contrary, this time he wanted her to write a letter on his behalf.

“Then let me get my ink and nib,” she said, as she corralled the pallid consumptive infants back into their cupboard so she would be able to write undisturbed.

“Dear Pamphleteer,” dictated the sludge person, as Mistress Spinoza inscribed his words in her neatest copperplate, “I know how to move sludge and I am going to put you to death for threatening my livelihood and injuring my pride, exclamation mark.”

He had lain upon his filthy mattress all night, embittered and impassioned, devising the exact wording for his letter, and now that it was written he sat back on the sawdust of the schoolroom floor, smug and content, as if the threatened deed had already been accomplished. Then he noticed that the schoolmistress was peering at him, and the look on her face was one of dismay and contempt.

“This will never do,” she announced, tearing the letter to shreds before the ink was even dry, “I will not be party to threats of violence. You ought to be ashamed of yourself. I have a good mind to lock you in the cupboard with the urchins. In fact, that is exactly what I am going to do.”

Mistress Spinoza was a slight woman, rake-thin and not much taller than the tots she taught, but she had inherited inhuman physical strength from her parents, a pair of circus artistes known professionally as Herculean Strongman Gervase Spinoza And His Equally Herculean Wife Constance. Now, their daughter picked up the peasant by his grubby collar and deposited him in the cupboard. No sooner had she done so than Dobson appeared.

“You are harbouring a peasant who has threatened me with death!” he announced, “And I know this is so because I have been experimenting with a futuristic telepathy device made of rubber, gutta percha, funnels, wiring, batteries, Coddington lenses and complicated electric circuitry. Ha!” — at this point he pointed to the torn up scraps of the letter in Mistress Spinoza's waste paper basket—“Can you deny it is so?”

Without a word, Mistress Spinoza led the fuming pamphleteer to the kitchenette, took the rags out of his ears, and made him a nice cup of tea, which she laced with six droplets of Baxter's Terrible Liquid Nerve Suppressant, “guaranteed” — according to the label—“to render the most tempestuous hot-head comatose for up to a week”. This had been purchased from a reputable supplier, and Dobson soon fell into a swoon.

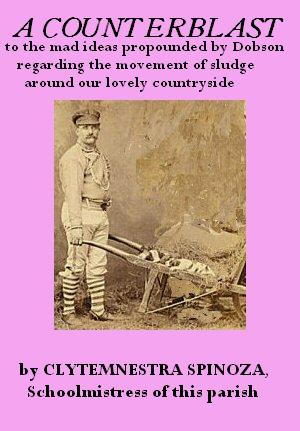

Later, the resourceful schoolmistress let the peasant out of the cupboard and had him load Dobson onto his wheelbarrow and take him home. Then she sat down at her escritoire and fired off a pamphlet of her own, entitled A Counterblast To The Mad Ideas Propounded By Dobson Regarding The Movement Of Sludge Around Our Lovely Countryside, and sent one of the urchins off with it to the printers.

By the time Dobson woke up six days later, all the talk in the village was of Mistress Spinoza's bonkers but brilliantly-argued philippic. No one was interested anymore in half-baked schemes to revolutionise the movement of sludge around the lanes of Mustard Parva. Dobson turned his attention to other things (jawbones, knitwear, Hedy Lamarr), and as dusk fell on that hot, sun-battered day, the sludge person, no longer embittered, could be seen pushing his wheelbarrow piled high with sludge up Pang Hill towards the orchard, as he and his ancestors had always done, and always would, throughout eternity, like Sisyphus.

*NOTE : This may have been the same peasant who planned to sell Mary Goldchew, the Savage Infant of Splat, to a zoo. See Feral Childhood, 30th March.

DETOURS : The Child's Day … Curiosities Of Literature … Hunkin's Experiments